STORY BY SANDRA S. SORIA ✷ PHOTOGRAPHS BY JONAS JUNGBLUT

Edith Heath may very well be the most influential American design icon you’ve never heard of.

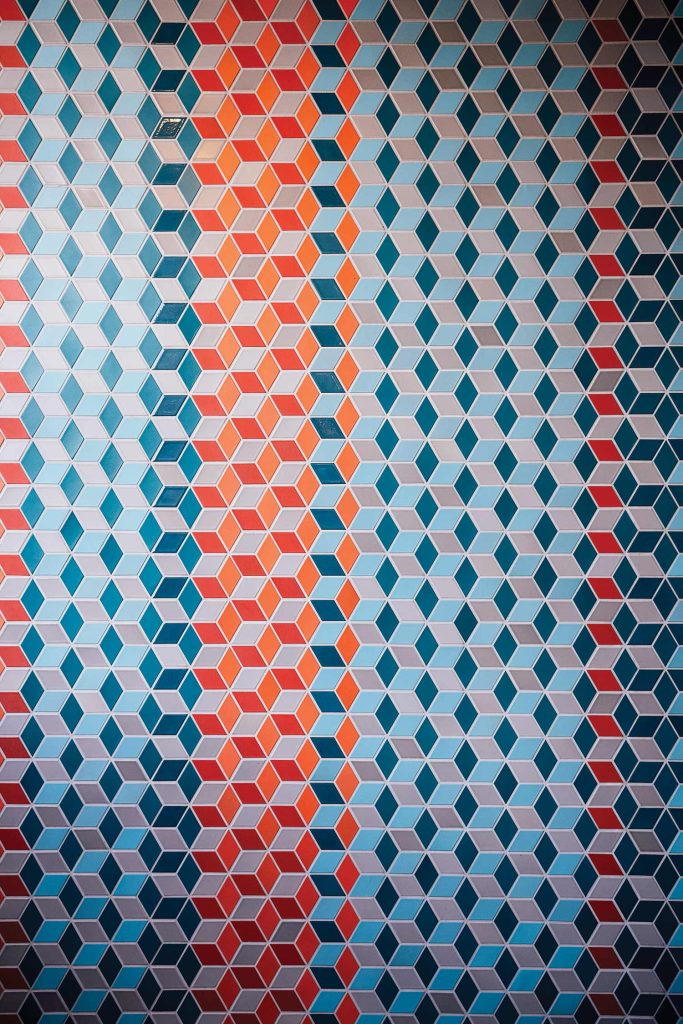

But you know the potter’s wares: Sturdy stoneware tabletop objects and tile that are unadorned and distilled in form, designed to celebrate their earthen materials and the hands that shaped them into something both artful and utilitarian.

It’s a style that’s been copied countless times, rolled out in big factories and on individual potter’s wheels. But when Edith and her husband Brian (who oversaw manufacturing) created the first Heath Ceramics line for Gump’s department store in 1948, it was a radical departure from the pattern-heavy Staffordshire or ubiquitous gold-rimmed china in favor at the time. Like other mid-century modern designs of that post-War era, countering the fancy, pinky-up designs was the point.

Edith was frank in her assessment of the premixed, commercial white clay imported from Europe that went into those delicate porcelains—it was “gutless.” She was, on the other hand, “looking for a clay that nobody knew anything about, that had unique properties that I could utilize and develop, that would be expressive of the region. I began to work with California clays that would turn out looking like something that nobody else had ever made.”

She found the winning earth in a clay pit near Sacramento and used it to create her signature mix, one that was coarser and stronger. She also developed glazes that could be fused with the clay in a single firing, pulling vessels from the kiln with matte, scratch-resistant finishes in earth tones that would be baked into home palettes for decades on tile as well as tabletops.

The first dinnerware design, Coupe, is still in production today. And it’s still on trend, embodying the modern, organic aesthetic that’s once again driving design. In fact, it joins the ranks of just a few American products that have been manufactured continuously for more than 50 years (think Levi’s 501s and Bausch & Lomb’s Ray-Bans). But it almost didn’t hit the milestone. In the early 2000s, the company was struggling and looking for buyers.

Enter Catherine Bailey and Robin Petravic, who purchased the company from the Heath trust in 2003.

Catherine and Robin seem like the perfect duo to be keeper of the Heath flame. Curiously, the married couple echo Edith and Brian Heath’s division of labor. Catherine’s professional background is in industrial design—she caught the eye of Nike before she even graduated from college and went to work for them practically the minute her degree was printed.

Robin was launched from Stanford University and a graduate program that married the art department with the mechanical engineering department. “I’m not a designer like Cathy, but much more tied to the manufacturing part of things and the making of things,”

he says.

So, when they were on a walk through their Sausalito neighborhood and stumbled upon the Heath Ceramics building with a “For Sale” sign tacked to it, it could have been serendipity. It was the modernist meets industrialist building itself that first caught their eyes. The structure—with studio, retail, and manufacturing space—had been completed in 1960 when the company was in full spin. It represented Edith’s vision of an ideal manufacturing space. It had an open, adaptable floor plan, a center courtyard, and windows that would allow for cross-ventilation, sunlight, and a view.

“I put a stake in the ground when designing color for dinnerware. It should last at least a decade.”

–Catherine Bailey

When they learned that the building housed an operational ceramics factory with a storied past, it drew the two in further. “It was a little dusty at the time,” Catherine says, “but we just kept asking questions. In our hearts we’re both preservationists. We really love history and trying to dig into what it means and what should be saved and what you should let go of.”

That process didn’t happen overnight. In part, because that’s not what preservationists-at-heart do. Especially preservationists that don’t go into a project with a lot of capital. “We didn’t come in with any kind of big investment.” Catherine says. “So, I was like, this is it, we’ve got to make it work from what’s here and fix what’s most critical. First, we had to fix the roof. There wasn’t any money to really scrap much.”

The lack of investment money was ultimately a positive—among other things, it allowed the couple to buy time. “It was a lot like an archeological dig,” Robin says. “For years we would find things that were informative, buried treasures in various nooks and crannies in this building. That’s how we got to know Brian and Edith and what drove them. It’s like buying a really old historic home and taking 18 years to fix it up rather than coming in with a big bankroll and construction crew to tear it down to the studs and build it over.”

Ultimately, they determined that the way forward was to focus on a transparently-sourced, small-batch ethos, pulling back from wholesale to focus on selling directly to the consumer online and through their company stores in the original Sausalito facility and newer outposts in San Francisco and Los Angeles. It’s a recognition that the product’s integrity wasn’t just tied to superior clay and glazes, but to a philosophy that recognizes that any profits they realize come at a cost to people and planet.

Even more, competing on price seemed to the two like a no-win situation. “I think this is what happened in manufacturing in America,” Robin says. “After a while, you had to figure out how to do more volume for less money. That’s what my early lessons in trying to run a business taught me, when big restaurant customers would come to me and keep trying to break the discount down and so on and so forth. The whole time I was like, this is a race to the bottom, there’s only one way this is going to end.”

So, they weaved their own “products with integrity” standard with Heath’s. They committed to paying employees a fair wage and offered them a stake in the company. Equally committed to sustainability, they hired staff that focuses on zero-waste initiatives. Selling directly to consumers meant they could control their packaging. With the furthest retail store in L.A., heck, they can load their van and drive product themselves to SoCal, which requires virtually no packaging at all.

It helps that the company is rooted in planet-friendly practices. They use the same California clay Edith did that requires only a single firing. The firing is also done at a lower temperature, racking up more energy savings. Perhaps a result of her “waste not, want not” Depression-era mindset, Edith used cast-off clay to make beads and smaller items that could be tucked into the kiln between larger ones so every inch was used.

These were some of the practices that landed in the “save” pile as Catherine and Robin dug through the company’s layers. It was a process that helped point the way to a future for the company. “It felt like a really clear path,” Catherine says. “We could understand why something started and what was really important about it. Then we just tried to weed out how things got distracted to get down to the pureness. It was also clear that this needs to be relevant today, we’re not trying to just make a nostalgic company.”

The Coupe design and other classic patterns in tabletop and tile remain, and many of the colors in the current line—Redwood, Opaque White, Sage, and Moonstone—date back to the early days of Heath. “To a lot of people, that’s their interpretation of Heath, a very ‘70s kind of a vibe. So, we still make all those,” Catherine says.

New additions to the line roll out thoughtfully, in keeping with Heath’s slow business model but also in recognition of how customers buy investment quality pieces. “I put a stake in the ground when designing color for dinnerware,” Catherine says. “It should last at least a decade. We believe it’s something you should build over time and that makes it more special. Rather than what happens so often in our current culture, where you buy a box of dinnerware and you’re good to go.”

Of course, pottery is art, where creativity and new expression are always invited to the table as well. This is where the Heath Clay Studio comes. Located in their San Francisco facility, Studio potters and glazers experiment at the wheel, creating limited and one-of-a-kind pieces. A few pieces might also make their way over to the factory.

Since Catherine and Robin took over the company in 2003, their slow and steady approach has meant a remarkable turnaround for Heath. When they took the wheel, there were 24 employees producing dinnerware and tile; now there are 170 employees at work in their people-over-profits company.

The light-filled Heath Clay Studio in San Francisco is a space where artists are allowed to “dream, take risks, and get their hands dirty,” creating work that ranges from one-of-a-kind, hand-thrown pieces to small collections of slip cast forms.

Though they’ve expanded the line to include other products—with a general rule of maintaining a formula of 70 percent dinnerware and 30 percent other home categories—they do so in partnership with only like-minded makers, such as flatware hand-tooled in New York by Sherrill Manufacturing. They’ve also polished up the brand’s cache through partnerships with big names that share their fresh and local ethos, such as a collaboration with another California pioneer, Alice Waters of Chez Panisse.

Retooling a legacy company, one that is also iconic, is no small feat. Catherine and Robin feel part of their success was that they could fly under the radar. “The company was doing things more to survive than focus on the iconic design legacy,” Robin says. “We didn’t feel pressure to do things a certain way because nobody was really watching. So, we could ask ourselves, if Edith were just doing the work that she loved to do, what would it be? And then bring that forward a little bit to be relevant today.”

There was a moment after they’d bought the company and before Edith died in late 2005, that the couple had a chance to get feedback from the icon herself. It was a stamp of approval of sorts, affirmation that they were steering the brand in the right direction. “We had this incredible moment,” Catherine says, “when she was brought to the factory by her caretaker Jay Stewart after we had purchased it. And she said, ‘This is amazing, they’re still making my designs.’ She completely acknowledged that we were continuing on in the spirit of her work. It was one of those moments where you can’t quite believe that this is all happening and it’s really significant.”